Wilms tumor is a solid cancerous tumor of the kidney. It is the most common form of kidney cancer in children.

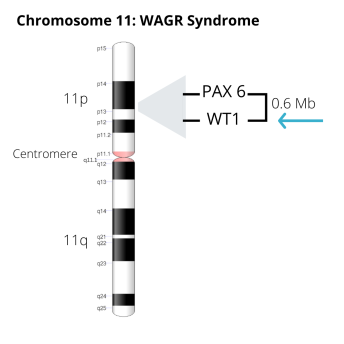

Children with WAGR syndrome are at increased risk for developing Wilms tumor. This increased risk is the result of a mutation in the WT1 gene, which is located within the region of the genetic abnormality that causes WAGR syndrome. About 50 percent of children with WAGR syndrome develop Wilms tumor.

It is not yet possible to predict which children with WAGR syndrome will develop Wilms tumor. For this reason, periodic screening for Wilms tumor should begin at birth or upon diagnosis of WAGR syndrome. Screening consists of abdominal ultrasound examinations every 3 months until age 8. Some physicians also advocate training parents to examine the child’s abdomen between ultrasounds.

Wilms tumor tends to occur at an earlier age in children with WAGR syndrome than in typical children. The average age of diagnosis of Wilms tumor in children with WAGR syndrome is 17-28 months and most cases of Wilms tumor in children with WAGR syndrome are diagnosed by age 3.

Although rare, Wilms tumor has been reported in individuals with WAGR syndrome up to age 19. For this reason, monitoring for Wilms tumor should continue throughout life. This surveillance may involve periodic ultrasound examination or MRI, and monitoring for symptoms such as abdominal mass, high blood pressure, and blood in the urine.

Treatment of Wilms tumor in individuals with WAGR syndrome involves a combination of surgery and chemotherapy. With early diagnosis and appropriate treatment, the overall survival rate for children with WAGR syndrome and Wilms tumor is excellent.

Printable Information Sheet

Wilms tumor may be suspected when a mass is seen in the kidney on ultrasound examination. However, "nephrogenic rests" (clusters of immature cells in the kidney) are also common in children with WAGR syndrome. Nephrogenic rests are not malignant, but their appearance on ultrasound or MRI imaging may make it difficult to determine whether the mass is a Wilms tumor or a nephrogenic rest.

Definitive diagnosis of Wilms tumor may require biopsy and microscopic study of the mass. Approaches to diagnosis and treatment differ somewhat in North America and Europe. For example:

Both of these approaches yield good outcomes.

Dylan undergoing routine ultrasound (with Dad)

Miranda undergoing routine ultrasound

Treatment of Wilms tumor usually involves a combination of surgery and chemotherapy. Sometimes radiation may also be needed.

Surgery is used to remove the tumor(s). Depending on the size and location of the tumor, the entire kidney may be removed. Difficult-to-remove tumors and bilateral tumors are often treated first with chemotherapy to shrink them and make them easier to remove.

Chemotherapy (“chemo”) uses powerful medicines to kill cancer cells or stop them from growing and making more cancer cells.

Jenna during treatment

Wes during treatment

The treatment plan for an individual patient depends on the characteristics of the tumor, including the stage of the tumor and its "histology" (microscopic structure).

It should be noted that in typical children, bilateral tumors (Stage 5) are associated with a lower rate of survival. In children with WAGR syndrome however, bilateral Wilms tumors are not uncommon, and survival rates are very good. The reasons for this difference are unclear, but may be related to routine screening and early diagnosis in children with WAGR syndrome.

For Wilms tumor that has returned (recurred), treatment depends on how far the disease has spread and which treatments were already used.

Navigating treatment for Wilms tumor can be scary and intimidating. The IWSA has compiled practical advice from parents to help families of children with WAGR syndrome get through treatment for Wilms tumor.

Cindy and Taylor, parents of children with WAGR syndrome

Nephrogenic rests are common in children with WAGR syndrome. A nephrogenic rest is a cluster of immature cells in the kidney that persists after birth. Nephrogenic rests are not malignant (cancerous) but they may sometimes transform into Wilms tumor.

“Nephroblastomatosis" is used to describe the presence of multiple nephrogenic rests.

In some cases, it is very difficult to distinguish nephrogenic rests from Wilms tumors on ultrasound or MRI imaging, or even with biopsy. It is also possible for a child to have both nephrogenic rests and Wilms tumor in one or both kidneys.

Although nephrogenic rests are considered benign, surgery and/or chemotherapy may be recommended if the nephrogenic rests are growing. Some evidence indicates that chemotherapy may decrease the risk for subsequent Wilms tumor development in children with nephrogenic rests.

Once treatment for Wilms tumor is completed, the main concerns for most families include whether the tumor will come back, and the potential for long-term effects from treatment.

It’s certainly normal to want to put the tumor and its treatment behind you and return to a life that doesn’t revolve around cancer. But it’s important to realize that follow-up care is a central part of treatment that offers your child the best chance for long-term recovery.

Your child’s health care team will set up a follow-up schedule, which will include physical exams and imaging tests such as chest x-rays, ultrasounds, and CT scans to look for return of the tumor or any problems related to treatment.

Since most children have had a kidney removed, blood and urine tests will be done to check how well the remaining kidney is working. If your child received doxorubicin (Adriamycin) during chemotherapy, the doctor will also order tests to check the function of your child’s heart.

The recommended schedule for follow-up exams and tests depends on the initial stage and histology (favorable or unfavorable) of the cancer, the type of treatment, and any problems that the child may have had during treatment. Doctor visits and tests will be more frequent at first (about every 6 to 12 weeks for the first couple of years) but the time between visits may be extended as time goes on.

During this time, it’s important to report any new symptoms to your child’s doctor right away, so that the cause can be identified and treated, if needed. Your child’s doctor can give you an idea of what to watch for.

Because of major advances in treatment, most children treated for Wilms tumor are now surviving into adulthood. Doctors have learned that treatment for childhood cancer can affect children’s health later in life, so watching for health effects as they get older has become more of a concern in recent years.

Just as the treatment of childhood cancer requires a very specialized approach, so does the care and follow-up after treatment. The earlier any problems can be recognized, the more likely it is they can be treated effectively.

It’s important to discuss what these possible effects might be with your child’s medical team so you know what to watch for and report to the doctor.

The risk of late effects of treatment depends on a number of factors, such as the specific treatments the child has, the doses of treatment, and the age of the child when being treated. These late effects may include:

As much as you may want to put the experience behind you once treatment is completed, it’s very important to keep good records of your child’s medical care during this time. Gathering these details during and soon after treatment is easier than trying to get them at some point in the future. There is certain information that your child’s doctors should have, even into adulthood, including:

Care management guidelines published in December 2022 outline specific recommendations for screening for Wilms tumor throughout the lifespan. These recommendations include ultrasound surveillance intervals depending on the patient's age and medical history.

Sign up for News & Events

COPYRIGHT© 2025 IWSA / International WAGR Syndrome Association